Reappraisal and Prosecution

Nuremberg trials

A year after the liberation of Germany, the victorious Allies held the Nuremberg Trials against the major Nazi war criminals. Among the accused were two Nazi officials responsible for forced labour under the Nazis, Fritz Sauckel and Albert Speer. Both were convicted and sentenced – Sauckel to death and Speer to 20 years in prison. Individual trials were also held between 1946 and 1948 against members of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WVHA), the heads of the Flick, I.G. Farben and Krupp companies, and Erhard Milch, who was State Secretary in the Ministry of Aviation.

Thwarted hopes of former forced labourers

After the creation of the two German states in 1949, the crimes of Nazi forced labour fell increasingly into oblivion. West Germany passed the Federal Compensation Act, which allowed victims of the Nazis to claim compensation. But the claims of former forced labourers were rejected on the grounds that forced labour was not recognised as a crime, but was justified as a necessary side effect of war. In addition, only people living in the West Germany were eligible to apply for compensation. West Germany paid compensation in the form of global agreements to individual countries, but no individual compensation was paid to former forced labourers.

While East Germany defined itself as an anti-fascist state and granted honorary pensions – supplementary payments to the state pension – to those it recognised as “victims of persecution by the Nazi regime”, former forced labourers, most of whom lived in other countries, did not benefit at all. East Germany also made no inter-state compensation payments.

Public pressure and payments late in the day

In the 1990s, after the reunification of Germany, there were calls for boycotts, collective legal action and compensation claims by former forced labourers against large German companies, particularly in the USA. This led to increased public discussion in Germany about the role of German companies during the Nazi era. Activists in history workshops, local associations and initiatives began researching the history of Nazi forced labour in their own communities and organising small exhibitions.

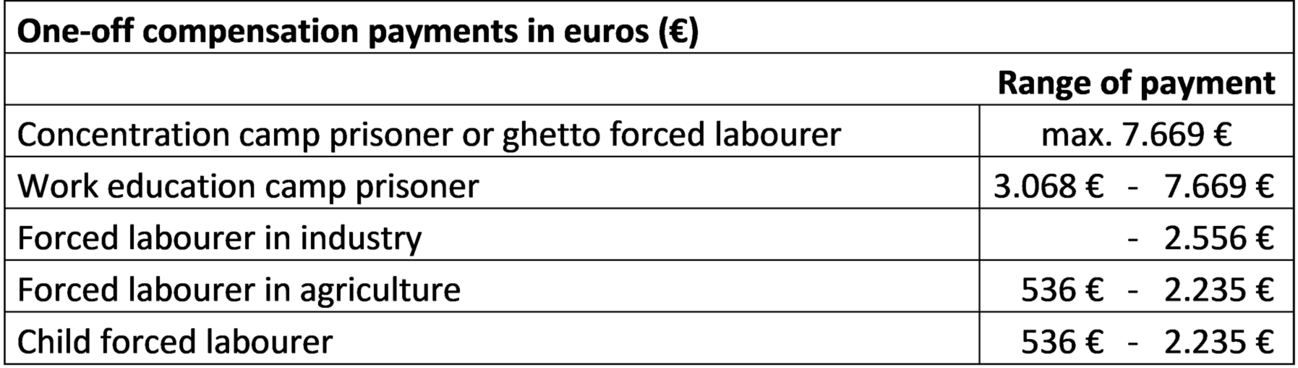

Public pressure culminated in the German government’s decision to set up a compensation fund. In 2000, it established the Foundation for Remembrance, Responsibility and Future (EVZ). The initial capital was 5.2 million euros, half of which was contributed by the German government and half by German industry. The companies, which included BMW, Bahlsen, Bosch, BASF, Deutsche Bank, Daimler-Chrysler, Lufthansa, Porsche, Siemens, Thyssenkrupp, Volkswagen and others, were then able to legally waive any future compensation claims and even deduct the payments from their taxes. One-off payments were made from this fund to former forced labourers. The payments ranged from 2.235 euros to 7.669 euros, depending on the type of forced labour the person had been forced to perform. Between 2001 and 2007, a total of 4.4 million euros was paid out to 1.6 million former forced labourers.

The compensation payments came too late for most former forced labourers. Many had already died. Moreover, not all victims were taken into account. Italian military internees and Soviet prisoners of war were excluded from compensation. This was justified on the grounds that Article 49 of the Geneva Convention allowed, in principle, the use of prisoners of war as labour.

In 2015, after ongoing political struggles over the politics of remembrance and after continued demands by activists, the German parliament decided that former Soviet prisoners of war would be included in the compensation payments. At the time of the decision, however, it was estimated that only 4,000 of them were still alive.

Italian military internees are still denied any compensation. They have only been awarded personalised medals of honour in recognition of the injustice they suffered – but only in Italy, not in Germany.

This means that most of those who were forced to work have never received any compensation. The companies that exploited people during the Nazi era have only had to hand over a fraction of the profits they made.

Further reading:

Henning Borggräfe. Entschädigung. Vom Streit um "Vergessene Opfer" zur Selbstaussöhnung der Deutschen, Göttingen 2014.

Constantin Goschler. Wiedergutmachung. Westdeutschland und die Verfolgten des Nationalsozialismus 1945 – 1954, München 1992.