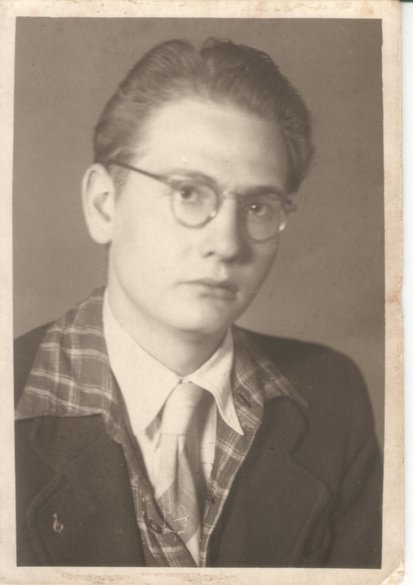

Klaas Touber (1922 – 2011)

Klaas Touber was born in Amsterdam on 27 June 1922. Before the war, he worked as a mechanic in the Jordaan district of Amsterdam. In 1943, he was contacted by the local labour office. Coercion was used to recruit Klaas Touber as a worker for the German armaments industry: the official in charge told him in no uncertain terms that his parents would be in danger if he refused to work in Germany. Faced with these threats, Klaas Touber decided to go to Germany that same year.

Klaas Touber was sent as a civilian forced labourer to Bremer Vulkan, a former shipyard in the Vegesack district of Bremen. Civilian shipbuilding had ceased there in the 1940s, and the yard was now used exclusively for military purposes. Klaas was forced to work there for two and a half years in various areas of submarine construction.

As a civilian forced labourer from Western Europe, Klaas Touber had a number of privileges compared to Eastern Europeans. For example, he had more freedom to move around the factory and the city. This enabled him to gain an impression of the living conditions of the Eastern Europeans. With a keen eye for detail, he described their systematic oppression in his memoirs:

"Deprived of all freedom, they were not allowed to leave the camp even after their work was done. Their food was worse than that of other foreign forced labourers. The ‘plain honourable Germans’ exploited the hunger of the Ostarbeiter by indulging their lust for Polish and Russian girls in exchange for a piece of bread."

– Klaas Touber’s memoirs, p. 162, original in Dutch

But Western European forced labourers too lived under the threat of arbitrary punishment and violence, or imprisonment in a penal camp. In 1940, at the insistence of some local industrial companies, one of the first work education camps (AEL) was set up. One day, after a German worker had pushed his way to the front of the queue, a fight broke out in the Bremer Vulkan canteen. Klaas Touber was severely beaten and his face disfigured by the German workers. The incident, however, led to the Gestapo intervening to punish the Dutchman. Klaas Touber was sent to the Farge work education camp.

What was probably his most difficult period as a forced labourer in the Nazi system began at Farge. Physical abuse, hunger and hard labour were the order of the day. After four months at the Farge work education camp, Klaas Touber was released and had to work at the Bremer Vulkan until the end of the war.

After the war, Klaas initially thought he had got through his years in Germany quite well. Reports of Auschwitz and other death camps made him reconsider his own suffering: other people had been much more severely affected by the war and Nazi rule. At first, he worked as a newspaper agent. He married and had two children. But as the years went by, problems in his life became more and more apparent. He had nightmares, was anxious and felt hunted. He was sent into early retirement at the age of 57, diagnosed with mental illness. The long-term effects of forced labour became increasingly apparent.

In 1983, at the suggestion of his wife, Klaas Touber returned to Germany for the first time, and by chance came into contact with a group of civilian war victims. This status allowed civilians in the Netherlands who had been affected by violence during the war to receive financial support. This contact helped Klaas Touber to realise that he too was a civilian war victim. It took a three-year struggle for him to be officially recognised.

Having obtained this recognition, in the summer of 1988 he also sought recognition from Bremer Vulkan. He wrote a letter in which he described the consequences of his forced labour and claimed a sum of DM 100 per month for the time he had spent as a forced labourer in the shipyard.

On 7 September 1988, he received a letter from the shipyard saying:

"It is difficult for us to gain an insight into the events of that time, which is now 45 years in the past. There is almost no documentation left from that time. Some Bremen historians, however, are trying to shed some light on that time, including by interviewing people." (Letter from Bremer Vulkan to Klaas Touber, 1988)

This statement not only shifted the responsibility for coming to terms with the past onto others, but also denied Klaas Touber any recognition of the injustice he had suffered. Despite an anger towards the German society of the perpetrators that was difficult to overcome, Klaas Touber campaigned for a living memory and reconciliation until his death in 2011.