Photographs: private commemorative photos by civilian forced labourers, registration photos and propaganda photos

Who took the photos and in what context were they taken?

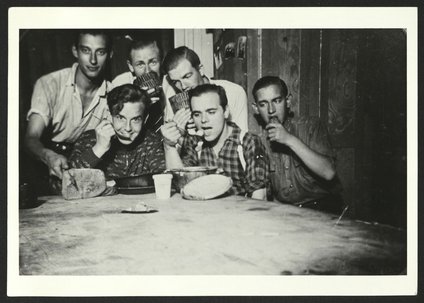

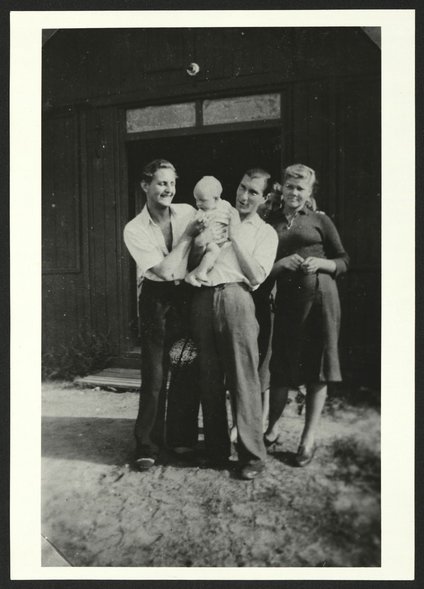

The first three photographs are private commemorative photos of civilian forced labourers. Photos 1 and 2 are from the collection of Dutch forced labourer Adrianus Markus. Markus was the only person in the Berlin-Spandau camp to own a camera. His photos record scenes from everyday life in the camp.

Photo 3 belongs to the Polish forced labourer Maria Andrzejewska, née Kawecka. It was taken in 1943 during a trip with other Polish forced labourers from the same Berlin factory. A German photographer was probably paid to take this picture of the group in front of the Berlin Cathedral.

What can we see?

In Photo 1, a group of young men is posing while eating. In Photo 2, two of the men are holding a young child. A woman is standing next to them. The mood seems relaxed. The group in front of the Berlin Cathedral in Photo 3 also makes a happy impression. All the people shown have a neat appearance. It is not obvious that they are forced labourers.

What do private photographs reveal about Nazi forced labour and what should be considered when using photographs in educational work?

The three private commemorative photographs record positive experiences and moments during the period of forced labour. They show the forced labourers as historical actors with agency who made use of the little freedom they were allowed. Keeping up appearances, having neat clothing and enjoying leisure activities together were coping strategies and expressions of self-assertion in a daily life marked by exploitation, humiliation and violence. In doing so, the forced labourers also disobeyed German prohibitions. The civilian forced labourers in photo 2 are two Dutch men and a Soviet woman with a child. Contact between them was forbidden. Photo 3 is also an example of the many encounters between forced labourers and the German population.

What do we not see?

Forced labour and violence are absent from these three commemorative photographs. It was almost impossible for forced labourers to document these parts of their daily experience. Photography was forbidden in the factories. These three photographs illustrate the fact that a photograph can only ever show a small part of the life of a forced labourer. If we are lucky, we know who took the photo, in what context and for what purpose. The subject of the photo also gives us an indication of the perspective from which the photo was taken and the purpose for which it was taken.

Besides private commemorative photographs, a wide range of other photos were taken in connection with Nazi forced labour: registration photos taken by the police, government agencies and companies; propaganda photos taken by companies and press photographers; private photos taken by the German population, often showing forced labourers only by chance; and photos taken by Allied photographers.

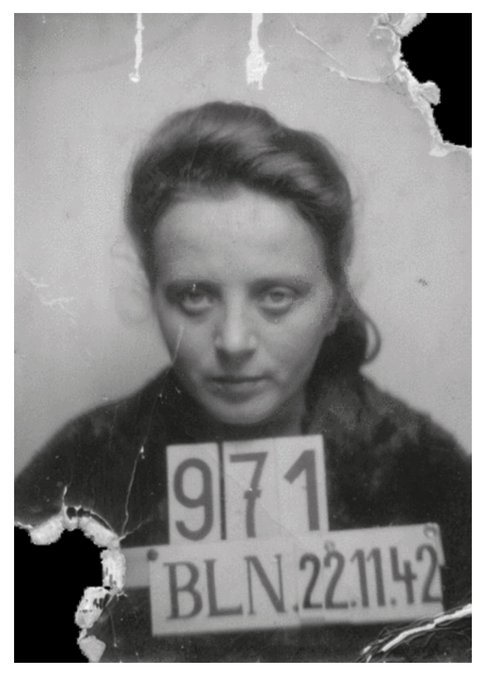

The perspectives and purposes of the photographs are fundamentally different. Registration photos were taken by the perpetrators against the will of the subjects. The photos were part of the bureaucratic organisation of forced labour and also enabled the monitoring and persecution of forced labourers. They were also used in connection with racist discrimination and stigmatisation. This example is a registration photograph of Maria Andrzejewska. It was taken after her deportation to the German Reich on 22 November 1942 at the Berlin-Wilhelmshagen transit camp.

Companies also had photographs taken for propaganda purposes. These photographs whitewash the living and working conditions of the forced labourers and are intended to demonstrate the orderly organisation of the work in order to present the company and the employer in a positive light. The photograph selected here shows a group of women, children and men from the Soviet Union arriving at Meinerzhagen in the Sauerland region of Germany on 29 April 1944. Some of them are showing off the food they have just received. At the time the photo was taken, this group had already undergone the degrading process of registration at the transit camp in Soest. There they had been “chosen” by “their” employer and taken to a company camp for Soviet forced labourers. Now the men, women and children are standing in front of a barrack hut, waiting to be assigned to their accommodation and workplace.

Literature

Pagenstecher, Cord: „Erfassung, Propaganda und Erinnerung. Eine Typologie fotografischer Quellen zur Zwangsarbeit“, in Reinighaus, Wilfried und Reimann, Norbert (eds.): Zwangsarbeit in Deutschland 1939-1945. Archiv- und Sammlungsgut, Topographie und Erschließungsstrategien. Bielefeld: Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, 2001, pp. 254-266.

Pagenstecher, Cord: „Privatfotos ehemaliger Zwangsarbeiterinnen und Zwangsarbeiter – eine Quellensammlung und ihre Forschungsrelevanz“, in Meyer, Winfried und Neitmann, Klaus (eds.): Zwangsarbeit während der NS-Zeit in Berlin und Brandenburg. Formen, Funktion und Rezeption. Potsdam: Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, 2001, pp. 223-246.