Personal testimonies by forced labourers: diary of the French prisoner of war Jean-René Vidal, letters from forced labourers

Who produced the document and in what context was it produced?

Jean-René Vidal (1905-1983), a trained carpenter from the Bordeaux region, was drafted into the French army on 28 August 1939. The Wehrmacht captured him near Paris in June 1940 and interned him in the prisoner of war camp Stalag III D in Berlin. There, he was forced to work in numerous labour detachments, first as a prisoner of war and then, from October 1943, with the status of a civilian worker. After being liberated, he returned to his home village of Bazas on 30 May 1945.

Vidal kept a diary recording his experiences during his time as a POW and forced labourer. The German translation of excerpts from this diary was published in 2017 as Ein Spielball in den Wirren des Krieges – Tagebuch eines Kriegsgefangenen (“A Pawn in the Turmoil of War: Diary of a Prisoner of War”). The book also includes more of Jean-René Vidal's memories, written down by his son Hervé.

What can we see?

The diary comprises eight notebooks in all, although the seventh is missing. The chronological entries begin on the day Vidal was into the army and end on the day of his return to France. A recurring theme is his concern for his family and the difficulty of staying in touch with them. Most of the entries deal with his experiences of working in the various labour detachments in Berlin and changing from one detachment to another, which often meant moving to a different camp, his relationships and leisure activities with other French prisoners of war and civilian forced labourers, and his recurrent bouts of illness due to the miserable working and living conditions. He frequently makes bitterly ironic comments on his situation. Thus, his entries give us an impression of his personality and reflect how his self-perception and mood change over the course of the five years.

What does the diary reveal about Nazi forced labour and what should be taken into account when dealing with personal testimonies in educational work?

The diary gives us a subjective impression of the situation of French prisoners of war and civilian forced labourers in Berlin in the period from 1940 to 1945 It also shows that the author, Vidal, was able to organise himself in such a way as to be able to keep a diary. There seems to have been plenty of paper and pens, and he seems to have had enough free time to write.

The writers of personal testimonies appear as actors who think and feel. This makes these documents particularly useful for understanding how people assessed themselves and their situation, and what strategies they used to cope with their situation. They also give us important information about the living conditions of forced labourers that cannot be gleaned from perpetrators' documents, which reduce forced labourers to their role as labourers.

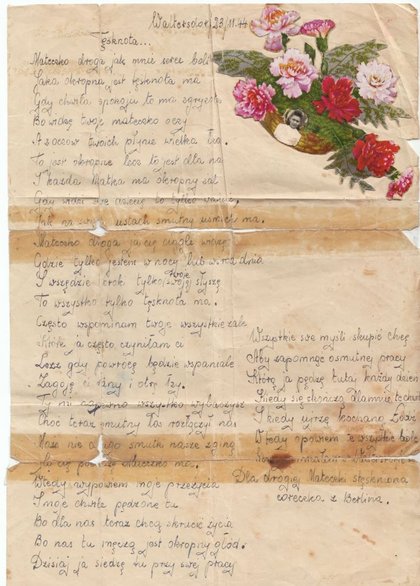

Personal testimonies can be divided into sources from the Nazi period and sources created after 1945. As well as diaries, forced labourers wrote countless letters during their period of labour. Deportation to the German Reich meant for them separation from their families and social environments. Writing letters was their way of trying to stay in touch with their families. As correspondence was subject to censorship, they could not write about everything they experienced. Many tried to paint as positive a picture as possible so as not to worry their families. A letter written by Polish forced labourer Alicja Nabiałczyk to her mother on 23 November 1944 shows that they did write about the painful experiences of separation and forced labour. Nabiałczyk wrote the text as a poem and gave it the title “Longing”.

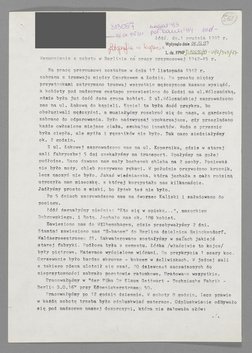

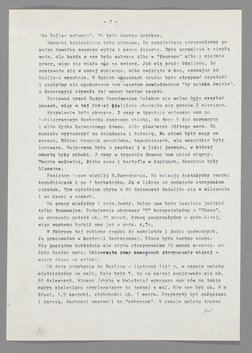

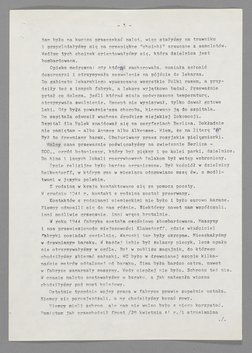

After 1945, countless testimonies were produced in the form of written recollections and video interviews. To support their claims for compensation, many former forced labourers wrote letters describing their daily lives in the camps and at work as evidence of what had happened to them. One example is the letter written on 1 December 1997 by the Polish civilian forced labourer Maria Andrzejewska, née Kawecka, to the Berlin History Workshop, in which she describes her deportation to the German Reich and her experiences as a forced labourer in Berlin from 1942 to 1945.

What do we not see?

Personal accounts describe situations from the subjective point of view of one person. Simply because people are in situations where they have limited access to information, this means that dates, people and events are sometimes misrepresented. This is all the more true when we are dealing with memories written down much later. With the benefit of hindsight, we often remember things that are important to us now in the present, or to the way we want to see ourselves and be seen. We often suppress things we might be ashamed of. Autobiographical narratives therefore tell us a lot about the person telling the story. In their stories they create images of themselves that can help them to make sense of things they have experienced, to understand them and then to come to terms with them.

Letter from former forced labourer Maria Andrzejewska, née Kawecka, dated 1 December 1997 to the Berlin History Workshop © Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit/Collection Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt, dzsw1488, with translation

Literature

Jean René and Hervé: Ein Spielball in den Wirren des Krieges. Tagebuch eines Kriegsgefangenen. Saint-Denis: Edilivre, 2017.

A digitalised copy of the original diary is on the website of the Archives départementales de la Gironde in Bordeaux: archives.gironde.fr/ark:/25651/vta0a782a4206ca9b62

Keller, Rolf: „Kriegsgefangene in der Reichshauptstadt: Das Stalag III D Berlin im Lagersystem der Wehrmacht“, in: Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit Berlin (ed.), Vergessen und vorbei? Das Lager Lichterfelde und die französischen Kriegsgefangenen. Berlin: Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit Berlin, 2022, pp. 20-31.